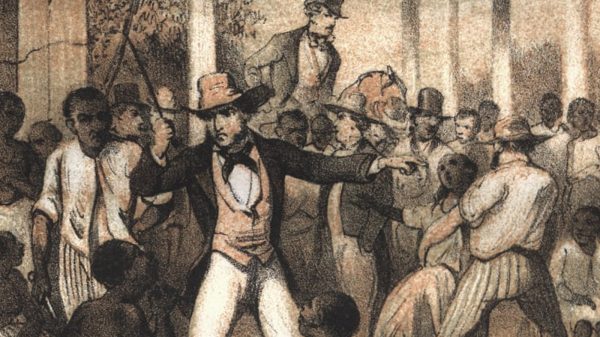

For thousands of years, slavery was an essential part of pagan Europe. The peoples of Ancient Rome and Greece understood that the existence of slaves was a natural necessity of society. Until the day when the breeze of a gentle but relentless revolution called the Christian Faith began to blow.

Here is the miracle: even without coming face to face with the laws and public power Christianity swept the slavery of an entire continent. It was a process of gradual and successive victories, which took centuries to consolidate.

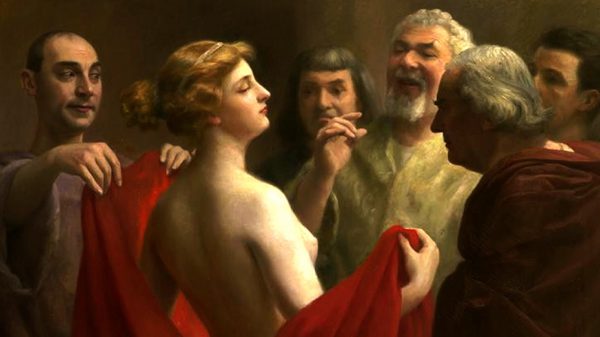

The thought that supported the slave system in Classical Antiquity was that the slave was an inferior being. Check out the writings of some of the most important pagan authors:

- Homer says, in Odyssey (17): “Jupiter has taken half the mind from slaves”;

- Plato: “It is said that in the spirits of slaves there is nothing healthy and whole, and that a prudent man should not rely on this caste of creatures, something that attests the wisest of our poets” (Diál. 6, Das Leis );

- Aristotle, in his Political work: “So it cannot be doubted that there are some men born for freedom, while there are others born for slavery …”.

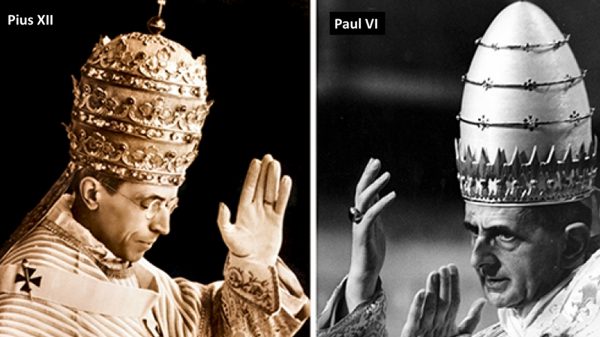

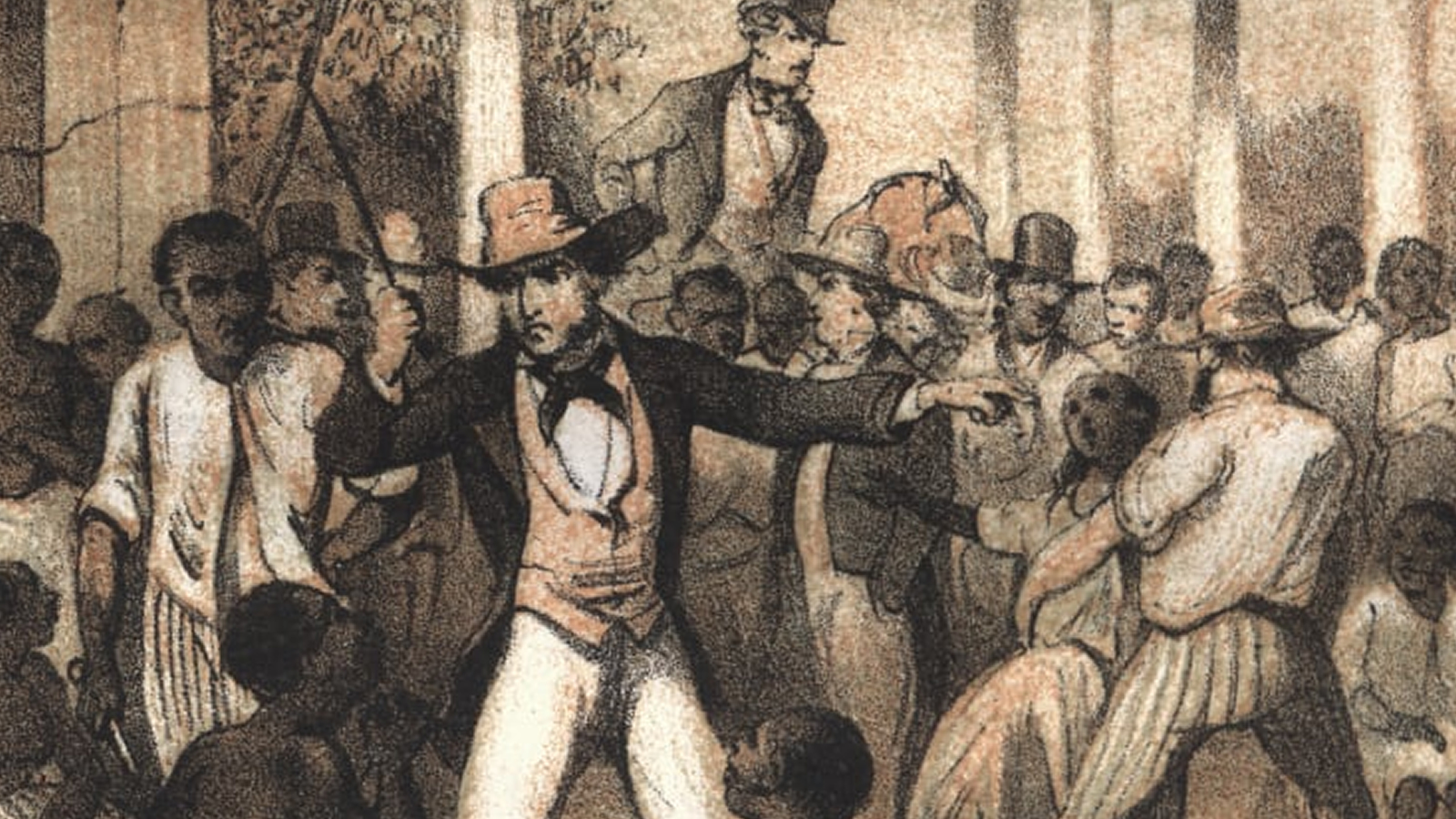

Instead of directly opposing the slave system – which would generate war and chaos -, the Church attacked the bases of this evil. Thus, it promoted the relentless and continuous corrosion of the slave’s culture of reification.

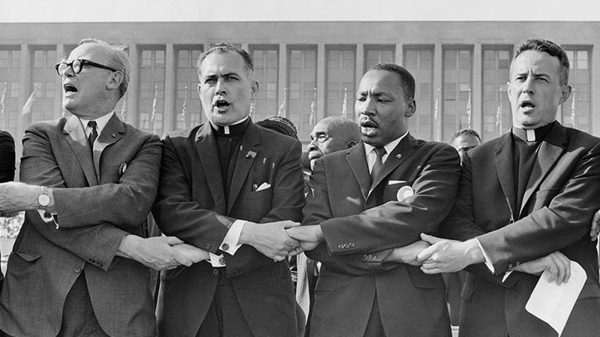

The Church has not sparked any movement of direct disobedience to slave laws. It was simply applied in spreading the doctrine that in Christ, all are brothers, and that God is no respecter of persons. As this mentality gained ground in civilization, slavery became an unacceptable shame.

Below, we point out some of the measures that were part of the Church’s educational action against slavery, in the period that preceded the Middle Ages.

- At the Age Council, in 506, it was defined that the Church, when necessary, should defend freed persons, who often suffered the threat of returning to the condition of slaves.

- The Council of Epaona, year 517, determined that whoever killed his slave would be excommunicated for two years.

- At the Council of Orleans, in 549, it was established that if a slave who committed a fault and took refuge in a church, he would be returned to his master only if he swore not to impose physical punishment on him. If the oath was broken, the perjured master would be excommunicated.

- The Lyon Council, year 566, provided for excommunication to anyone who captured free people to enslave them.

- At the Council of Mâcon, in 585, it was established that priests should rescue the captives, using the assets of the Church (purchase of manumission).

- At the Council of Rome, in 597, Pope St. Gregory guaranteed freedom to slaves who wanted to be monks, as long as the authenticity of their vocation was verified.

- The Council of Reims, which took place in 625, provided for the suspension of duties from the bishop who sold the sacred vessels (objects used in the liturgy), but made the reservation: “… unless for the reason of redeeming captives”. That is, unless the sale had the purpose of obtaining money to pay for manumission.

According to Hilaire Belloc (in his book The Servile State), in the beginning of the 9th century slavery was practically extinct in Christian Europe. The servant had access to the means of production, and, after paying tribute to the master, he could negotiate the surplus production. In addition, it was linked to the land, and can never be traded as a commodity.

However, even in the early Middle Ages, slave traders persisted with their perverse activity in some locations. And the Church did not rest in its work. At the Council of Armagh (Ireland, year 1171), the bishops determined that all English slaves should be freed. The local Church pointed to the cause of a particular public calamity in the slave trade carried out by the Irish, which would have attracted divine punishment.

In Eastern Europe, however, the servile relationship was degraded. Schismatic, rebellious against the Pope, the Orthodox Church has lost much of its ability to radiate Gospel values to socio-economic relations. In Russia, for example, despite being called “serfs”, peasants were, in practice, slaves. Families were separated by selling “servants” to other masters, and torture and abuse were routine (on this, see the book Catherine, The Great: Portrait of a woman, by Robert K. Massie).

Church history shows us that in order to build a more just society, we do not need to cling to ideologies – which are often filled with anti-Christian values. It is enough for us to seek our personal sanctification, to preach the Gospel and to serve the most suffering with love.